The $15 Disposable Tech Dilemma: A Product's One-Year Lifespan and the Economics of 'Good Enough'

Update on Oct. 12, 2025, 5:27 p.m.

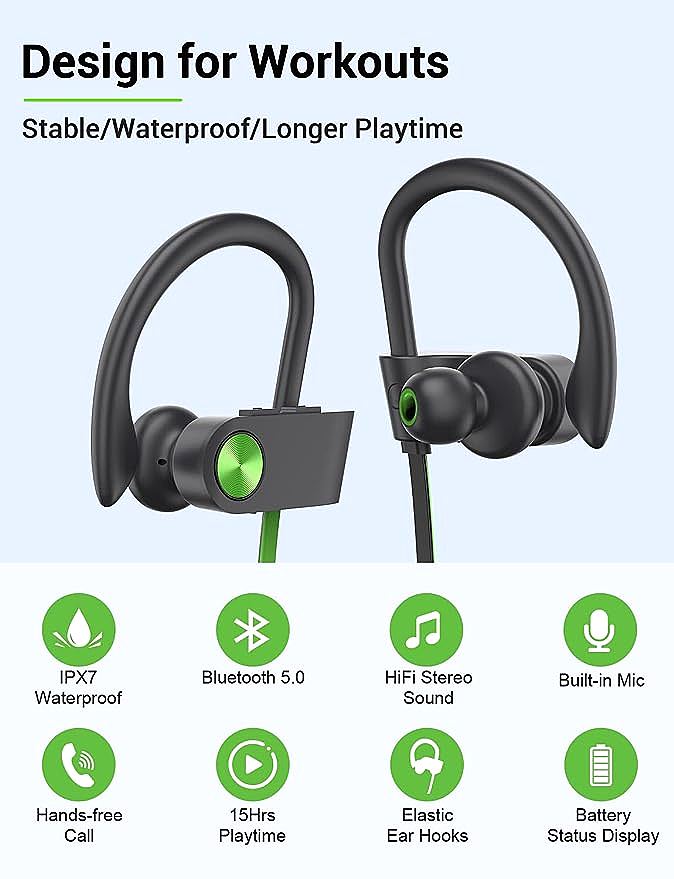

In the vast sea of online product reviews, amidst the usual chorus of praise and complaint, you occasionally find a comment that stops you in your tracks. It’s not a one-star rant or a five-star rave, but something far more revealing. Consider this review for the Stiive U8I wireless earbuds by a user named Carmelya: “Honestly they last about one year (again with daily use) before the sound starts only coming out one ear. However, I keep buying them every year because they are great and the battery lasts me all day long.”

Read that again. The product predictably fails within a year. And the customer’s response is not anger, but annual repurchase. This isn’t a story of a disgruntled consumer. It’s a story of a satisfied one, whose satisfaction is predicated on an expectation of failure. This strange paradox is the key to understanding one of the most powerful forces in modern commerce: the rise of disposable tech and the economics of ‘good enough.’

The ‘Good Enough’ Revolution

For decades, the consumer electronics narrative was a relentless march towards more features, better performance, and higher quality—often with a price tag to match. But a parallel revolution has been brewing, driven by a simple principle: for a huge segment of the market, perfection is the enemy of ‘good enough.’

A $15 pair of earbuds like the Stiive U8I is a masterclass in this principle. It doesn’t offer the pristine audio of a $300 headset, nor the seamless multi-device pairing of a premium brand. It won’t have the most advanced noise cancellation. What it does offer is a checklist of core, non-negotiable functions executed to an acceptable standard. Does it connect via Bluetooth? Yes, and with version 5.3, it does so reliably. Does the battery last through a workout and a workday? Yes, a claimed 16 hours is more than sufficient. Is it resistant to sweat? Yes, the IPX7 rating provides peace of mind.

This is the ‘good enough’ proposition: it solves the user’s primary problems at a price point that makes its flaws and, crucially, its limited lifespan, not just tolerable but expected. The failure point—as Carmelya notes, one earbud dying—is likely due to a fine wire breaking from repeated stress, or a battery reaching its limited cycle count. These are not design oversights; they are the direct, predictable outcomes of intense cost optimization. Using a slightly more durable wire or a higher-grade battery might add only a dollar or two to the manufacturing cost, but in a market of razor-thin margins, that dollar is a mountain.

Planned Obsolescence vs. Cost-Driven Failure

It’s tempting to label this phenomenon “planned obsolescence,” a term that evokes images of shadowy engineers intentionally designing products to fail right after the warranty expires. While that certainly happens in some industries, what we’re seeing in the ultra-low-cost electronics market is often something more subtle: not planned obsolescence, but cost-driven failure.

The distinction is important. Planned obsolescence is an active strategy to compel future purchases by making a perfectly functional product seem outdated (e.g., through software updates that slow down older phones). Cost-driven failure, on the other hand, is a passive consequence of hitting an extreme price target. The goal isn’t to make the earbud fail in a year; the goal is to make an earbud that costs less than, say, $5 to produce. A one-year lifespan is simply the natural result of using components and manufacturing processes that fit within that unforgiving budget. The failure is not the plan; it is a known and accepted variable in the equation of radical affordability.

The Psychology of a $15 Bet

This economic reality fundamentally reshapes consumer psychology. When you buy a $300 piece of audio equipment, you are making an investment. You expect it to last for years. You scrutinize its build quality, its warranty, its feature set. A failure feels like a betrayal.

But a $15 purchase isn’t an investment; it’s a bet. It’s a low-stakes gamble. This psychological reframing does several things: * It Lowers Expectations: You implicitly understand that you are not buying heirloom quality. The focus shifts from longevity to immediate utility. * It Minimizes ‘Buyer’s Remorse’: If the product fails, the financial loss is negligible—less than the cost of a few cups of coffee. The emotional energy required for a warranty claim or a lengthy support chat often outweighs the value of the product itself. * It Fosters a ‘Consumable’ Mindset: The earbuds are no longer a durable good, but a consumable, like printer ink or razor blades. Their eventual failure and replacement become part of the expected user experience.

This $15 bet is a psychologically comfortable one. If it fails, the loss is negligible. This transforms our relationship with the product. But while the cost to our wallet is low, the collective cost of this ‘disposable tech’ model is mounting elsewhere—in landfills, in resource depletion, and in the very definition of quality.

The Hidden Costs of Disposable Tech

Every year, the world generates over 50 million metric tons of e-waste, a toxic tide of discarded circuit boards, batteries, and plastics. Products designed for a one-year lifespan are a significant contributor to this crisis. Their low cost disincentivizes repair—it’s almost always cheaper and easier to replace than to fix.

This model also creates a challenging environment for innovation focused on durability and sustainability. Why would a company invest in engineering a five-year earbud if the market has been conditioned to happily replace a one-year model? The “good enough” revolution, for all its accessibility, risks trapping us in a cycle of mediocrity and waste.

Conclusion: Conscious Consumption in a Disposable World

The story of the annually repurchased Stiive U8I is not an indictment of a single user or a single brand. It is a perfect snapshot of a complex, global economic system. It highlights the incredible power of accessibility, allowing more people than ever to enjoy the benefits of wireless technology.

But it also forces us to ask difficult questions. What is the true price of “cheap”? How do we balance affordability with responsibility? There are no easy answers. But the first step is awareness. The next time we are faced with a choice, we can look beyond the price tag and ask ourselves not just “Is this good enough for now?” but “What is the cost of ‘good enough’ in the long run?” The decision is still ours, but a conscious choice is always a more powerful one.